-Vagish K Jha

“The real ceremony begins where the formal one ends, when we take up a new way, our minds and hearts filled with the vision of earth that holds us within it, in compassionate relationship to and with our world.”

These words of Linda K. Hogan, a Native American poet, keeps ringing in my ears as I participate in any ritual or ceremony. The Republic Day celebration on 26th January is one such occasion. As a teacher I wonder as to how young and old alike can be filled with vision for a new way, our minds and hearts can develop a compassionate relationship with the world we live in; with the nation for which we unfurl the flag and sing our anthem for! Allow me as a teacher to engage in a quick reflection of on the Republic Day of India.

As a teacher I am worried that much of the significance is lost when a ceremony like Republic Day becomes a routine ritual and children are not curious to know what is a Republic? I am also apprehensive if my students may not think it to have some connection with ‘chicken republic’ or ‘Republic of Chicken’, popular eating joints in some cities! As a teacher I don’t like to take such ideas or things on their face value.

Rather than taking it for granted, it would be fascinating to know that as of 2017 out of the world’s 206 sovereign states there are 159 countries who use the word “republic” as part of their official names. All these republics don’t necessarily have an elected government, nor do they have similar kinds of democracies in action. We could, for example, let’s look at the interesting case of the Arab Republic of Egypt whose President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was the Chief Guest of this years’ (2023) Republic Day parade.

Even a quick comparative study of some States with the epithet ‘Republic’ would tell us a fascinating story about the political systems. If only we could get out of the fetish of syllabus to allow our students to look around and engage in an exercise like this, it would give us a deep insight to develop a perspective on the nature of States and our understanding of political science as such. This would make our teaching learning more engaged and contemporary.

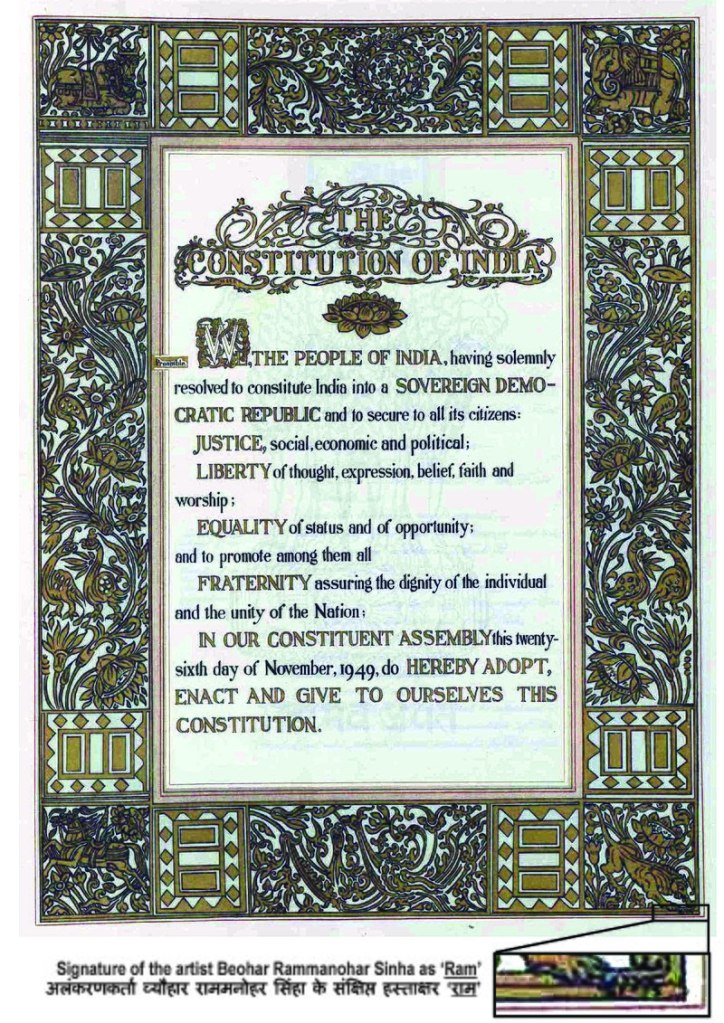

In Indian context the word republic is associated with the adoption of constitution. Though India became an independent nation on the 15th August 1947, it wasn’t until January 26, 1950, that the Constitution of India came into effect. To frame the constitution, the Constituent Assembly came into being which held its first session on December 9, 1946, and the last on November 26, 1949. It was only then that India became a sovereign state with the constitution if India declaring, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a union of States.” Dr BR Ambedkar headed the Drafting Committee of the Constitution. Here I am tempted to quote Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s concluding remarks in the Constituent Assembly on Constitution on November 25, 1949:

“On the 26th of January 1950, India would be a democratic country in the sense that India from that day would have a government of the people, by the people and for the people. The same thought comes to my mind. What would happen to her democratic Constitution? Will she be able to maintain it or will she lose it again. This is the second thought that comes to my mind and makes me as anxious as the first.”

Why was Dr Ambedkar so anxious?

There are reasons that statesman like him foresee, as it were. The fate and future of a nation is not contained in the book of constitution. It is people of the nation who remain aware and alert about protecting the ideas and ideals. If we look at the word ‘constitution’ as a set of guiding principles and rules of governance, it has varying types and manifestations. Having a constitution does not make it a republic or democratic. Historically there was constitution of Roman Kingdom. Constitution in the Roman kingdom was a set of guidelines and principles originating mainly through convention of what has been happening earlier. This system of kingdom was replaced by Roman republic. Again, here the word republic doesn’t represent what Republic means for India or the world in the modern sense today.

Words are shifting sand of meanings. They evolve and derive meanings in specific contexts. Examining a word and associated meanings is also an opportunity to understand the dynamic nature and evolution of meanings of a term like republic.

Historically the term ‘Republic’ is the Latin translation of Greek word politeia which was translated as res publica, which literally means “public thing”, “public matter”, or “public affair”. In Greek Republic it meant a political system as a state in which people, or their representatives wielded political power rather than being run by a hereditary monarch or king. In this sense, India has had many a republic even before the Roman ones.

In the same speech as cited above, Dr Ambedkar says, “There was a time when India was studded with republics, and even where there were monarchies, they were either elected or limited. They were never absolute. It is not that Indian did not know Parliaments or Parliamentary Procedure. A study of the Buddhist Bhikshu Sanghas discloses that not only there were Parliaments—for the Sanghas were nothing but Parliaments—but the Sanghas knew and observed all the rules of Parliamentary Procedure known to modern times. They had rules regarding seating arrangements, rules regarding Motions, Resolution, Quorum, Whip, Counting of Votes, Voting by Ballot, Censure Motion, Regularization, Res Judicata, etc. Although these rules of Parliamentary Procedure were applied by the Buddha to the meetings of the Sanghas, he must have borrowed them from the rules of the Political Assemblies functioning in the country in this time.”

Apart from the Buddhist Sanghas, there are other instances in ancient India which are alluded to represent democracy. For example, on 10 December 2020, while laying the foundation stone for an ultra-modern triangular Parliament building Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said, “India’s democracy is a system developed through centuries of experience.” He was citing the example of the Chola period Uthiramerur stone inscription written in Tamil which mentions elaborately about the process of local governance prevalent there.

Here, we need to pause and examine the idea of democracy. Rather than talking about democracy in abstract and philosophical terms, which, nonetheless, is a fascinating way to approach it, let us quickly see this issue in a historical perspective before we come to its modern context.

Students of history are aware that Village assemblies were crucial to Chola administration. Those living in the usual peasant villages met in an assembly called the ‘Ur’, whereas those from the Brahmadeya villages, the villages given to Brahmanas as a gift, used the superior title of ‘Sabha’. Though royal officials were present at the meetings of the sabha but their role was more as observers and advisers.

The above inscription underlines the fact that there was a fair degree of autonomy at the village level. It lays down the procedure of qualification for a candidate to contest the elections of the ward and various committees. It also states how the elected representatives can be called back. “Anyone on a Committee found guilty of an offence shall be removed at once”, states the inscription. It articulates detailed rules to ensure wider representation by forbidding close relatives of the contesting candidates from elections to prevent nepotism. The full transcription of the inscription is cited by Romila Thapar in her most popular book.

Yes, there was an elaborate system of election with an eye on fair representation in the system mentioned in the inscription. But how does it compare with the modern notion of democracy?

To cite one example from the inscription itself about the qualification of those who could contest the election, we find interesting criteria. The inscription says, “He must own more than one quarter of the tax-paying land. He must live in a house built on his own site. His age must be below seventy and above thirty-five. He must know the mantras and Brahmanas [from the Vedic corpus]…”

I often give this passage to my students when we discuss democracy. It has always invariably led to an animated discussion. Students are quick to point out that this violates the principle of equality, ‘one-person, one-vote’. While most agree that the clause of wealth is discriminatory, there is a serious difference of opinion on education as a qualifying criterion. This exercise leads to a deep examination of the term ‘democracy’. Students soon realise that it is variedly understood and there are different systems of representation called democracy.

So, once a student asked me – “Sir, can something be democratic and unfair at the same time?” I would leave this exciting question for my readers to debate and discuss.

Another important point that emerged was that ‘democracy’ as a concept must not be limited to political affairs or the states. It should cover other kinds of groups and situations also. So, students might want to examine if classrooms and schools are democratic spaces, they might be interested in understanding the meaning of democracy in families, while trying to grasp its meaning for states and other global organizations.

The word democracy is a combination of two words – “Demos” means “the people”, and “kratia” means “rule”. But ‘Democracy’ is not a noun. It’s a verb! It needs to be understood how it is practiced. In broad terms, it is understood as a ‘method of collective decision making where everyone carries equal weightage and value and the decisions thus made are binding on all the members of the group’.

“What is the significance of the word ‘republic’, translated as Ganarajya in Hindi, in the Indian Constitution?”, a child wanted to know. The PM in his above speech also talked about ancient Ganarajyas like Shakya, Malla and Vejji, or Licchavi or the Kalinga in the Mauryan period and claimed that “all of them made democracy the basis of their governance.” This is what Dr Ambedkar had also referred to in the quote cited above. This, however, needs to be seen closely in terms of historical evolution.

In ancient times, we find two terms – gana-sangha or gana-rajya. In this, the term gana denotes people of equal status whereas sangha means assembly, or rajya refers to the system of governance. In practice these were systems where the heads of families belonging to a clan, or clan chiefs in a confederacy of clans, governed the territory through an assembly. So, when the power was vested in the small ruling families who alone participated in governance, can it be called a democracy? We often use another term to denote such a system – oligarchy which was distinct from monarchy. Equating ancient ‘republic’ is not the same as the modern term used in the Constitution.

So, we need to understand the meaning of the term ‘republic’ in our constitution in modern times differently than as understood in a federal system. The modern federal system refers to a kind of dual system of governance – there is a national government at the Centre with the other tier of governance at the state level. Thus, as a federal state, India is a fusion of several states into a single State. The central government has the primary responsibility to ensure matters of common interest whereas the constituent states have autonomy regarding other matters.

That way, there is a division of authority by way of distribution of power. So that such a system should not lead to conflict of interests, there is a supremacy of the Constitution that overrides both tiers of governance. And, finally, if there is still a difference of opinion about the constitution or its interpretation, we have an independent judiciary as an arbitrator with the final power to interpret the Constitution. That is why the sense in which Article 1(1) of Indian constitution says, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a union of States.”

But more than all these democratic institutions, which do play crucial role, it is the people of India, especially our children of today, need to understand and guard the spirit of constitution that envisioned India as a secular nation protecting the interest of all its citizens without prejudice or bias. This was the concern of our forefathers.

This was the anxiety of Dr Ambedkar in his speech of Constituent Assembly on December 9, 1946 cited above. He said with his characteristic clarity, “This anxity is deepened by the realization of the fact that in addition to our old enemies in the form of castes and creeds we are going to have many political parties with diverse and opposing political creeds. Will Indians place the country above their creed or will they place creed above country? I do not know. But this much is certain that if the parties place creed above country, our independence will be put in jeopardy a second time and probably be lost for ever. This eventuality we must all resolutely guard against. We must be determined to defend our independence with the last drop of our blood. (Cheers.)”

Let our fervour to observe the Republic Day ceremony keep us alert to guard the true spirit of India and contribute to build it on the corner stone of liberty justice, equality and secularism and develop a ‘compassionate relationship to and with our world.’

.