-Vagish K Jha

Let me share with you an amazing story:

girl fruit pick turn mammoth see

girl run tree reach climb mammoth tree shake

girl yell yell father run spear throw

mammoth roar fall

father stone take meat cut girl give

girl eat finish sleep

You, I am sure, must have understood it easily enough. If not, please go back to it again. This time read it slowly and pay attention as you read it. The story will clearly reveal its charm on you. Right?

Shorn of all the niceties of grammar like tense, particles, cases, preposition conjunction and like, this is simply a sequence of words grouped together and separated by spaces, yet it manages to convey a coherent story. This can be understood in any language. This story by historical linguist Guy Deutscher[1] doesn’t follow any rule, especially the basic English grammar rule of ‘subject-verb-object’. In fact, it violates them. Yet we can make out the story. Why?

In the unusual composition of this ‘story’, Deutscher used a few natural principles rooted in the deepest level of our cognition. He grouped words together to represent things that are closer in time or action like ‘girl’ and ‘fruit’. He arranged words according to the order of the events. He also used, and you may wonder, the most common ‘subject -object -verb’ sequence. Yes. The studies have shown that human mind thinks in the sequence of subject first, then the object and then the action or verb. Only 10 percent of languages including English put the verb before the object. Thus, ‘girl fruit pick’ is easier to understand than ‘fruit girl pick’ or ‘pick girl fruit’. These simple organisational rules, Guy argues, would have been used by pre-verbal humans to tell a story using gestures. By using relational categories, we would no longer need to tell the story in the place where the events actually occurred and with all the characters are present. We can tell a convincing story of a time when horses could fly in a land that lies beyond the seven seas.

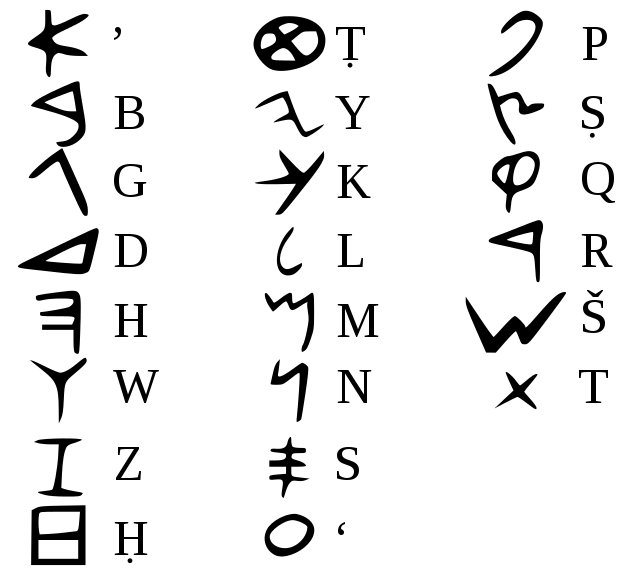

Language, you would agree, is a tool of extraordinary sophistication. It is a marvellous invention composed out of twenty-five or thirty sounds – p, f, b, v, t, d, k, g, sh, a, e and so on. These letters are nothing more than a few “haphazard spits and splutters, random noises with no meaning, no ability to express, no power to explain. But run them through the cogs and wheels of the language machine, let it arrange them in some very special orders, and there is nothing that these meaningless streams of air can’t do…”’[2].

If you consider the symbols constituted by letters such as A, C, T, they have no meaning by themselves, but they come alive the moment we join them in a particular order to become cat or act or tac. They combine to acquire infinite variety of expressions. These isolated letters have no likeness to what is in our mind. But they allow us to disclose to others its whole secret – what is there in our mind or what we are feeling.

The independence between sound and meaning is believed to be a crucial property of language. The sound produced while pronouncing the word dog has nothing to do with the actual dog as an animal. There is no intrinsic meaning of, say a prefix “un” or a suffix “er” or “ly” but when they join, with “like” it acquires a meaning in word ‘un-like-ly’. But the amazing world of language still throws many scholars to deep dive and find amazing patterns. So, scholars of late have found that despite the immense flexibility of the world’s languages, some sound–meaning associations are preferred by culturally, historically, and geographically diverse human groups.[3]

It is a common experience for us to notice that children master the basics of the phonetic system, grammar, vocabulary, and conversational principles of their native tongue in the span of a few short years. Children learn a language at a relatively predictable pace. It also follows a fairly regular pattern of acquisition, irrespective of the language to be learned or the cultural milieu in which they are raised. Until about 15 to 18 months, Lila Gleitman[4], a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania has found in her studies, children learn about one word every three days. After that, rather suddenly, they begin learning 10 words a day[5]. “By the age of four children master the use of specific words, styles, gestures and social conventions. They use appropriate pronouns for addressing people based on the context of talk, they use questions to enquire, exclamations to express surprise, they vary the stress on words depending upon their intentions, and they narrate events using narrative style, engage in dialogues, make arguments, read intentions of other people, negotiate, and respond depending on their motives and so on.”[6]

Language and literacy skills are the foundations for all cognitive processes required for leaning. “Therefore, meaning-making, thinking, and reasoning need to be a part of language and literacy development in early grades.”[7] It is pertinent to point out that the term ‘literacy’ is not about identifying letters or words. It refers to the interrelatedness of language–speaking, listening, reading, writing, and viewing.

Thus, reading is not merely ‘decoding’ and pronouncing the words. It is an act by which child reconstructs the meaning of the written or oral words. Thus, comprehension and meaning making are core ideas behind the literacy. Built upon this are other higher cognitive skills which include -making inference, abstracting the core idea(s), summarizing and retelling a story, applying ideas learned in one context to a new or different context, expressing an opinion about what is read or heard, organizing and presenting thoughts logically and thinking and writing or expressing creatively among others.

All these higher order skills, I invite you to consider, can be applied equally to listening and speaking as well as reading and writing. Reducing this to the act of reading or writing or ‘decoding’ letters sounds misplaced. By listening to the printed word, children can develop a feel for the patterns, the flow, and the nature of written language. Children receive a general sense of what reading is all about and what it feels like. This is what is known as ‘Emergent literacy’, a term introduced by Teale and Sulzby, to describe the reading and writing experiences of young children before they learn to write and read conventionally.[8]

The idea of emergent literacies challenges the old assumptions about language learning which believed:

- Literacy is learned in a predetermined, sequential manner that is linear, additive, and unitary.

- Literacy learning is school based.

- Literacy learning requires mastery of certain pre-requisite skills.

- Some children will never learn to read.

This assumption continues to haunt our language learning attitudes even today. But a major rethinking had started in the mid-sixties. It was Marie Clay , a researcher from New Zealand who observed that even before children are capable of reading in the conventional sense they employ early behaviours and concepts in interacting with books. She termed it Emergent Reading. This was followed by some robust research activity in children’s early language development and re-examination of the concept of reading readiness in the 1970s and early 1980s. Teale and Sulzby assembled a book authored by various leading researchers of the time. They proposed reconceptualizing what happens from birth to the time when children start reading and writing conventionally. They called it Emergent Literacy.

The basic components of emergent literacy include[9]:

- Print motivation: children get interested in and start enjoying books.

- Vocabulary: Children display keenness in knowing the names of things.

- Print awareness: They start noticing print, begin to know how to handle a book, how to turn pages and follow words on a page.

- Narrative skills: Children begin to describe things and events to tell stories.

- Letter knowledge: They can identify letters and tell one is different from the other, begin to know their names and sounds, and recognise letters everywhere.

- Phonological awareness: children can hear and play with the smaller sounds in words.

This transformed the understanding of Early Literacy Programmes (ELPs) and gave rise to ‘New Thinking’ that suggested that:

- Literacy is a process that begins at birth – there are no prerequisites.

- Literacy is learned through interaction with and exposure to all aspects of literacy (i.e. listening, speaking, reading, and writing).

- Literacy abilities/skills develop concurrently and interrelatedly.

- All children can learn to use print meaningfully.

Dr. Dhir Jhingran, Founder & Director of Language and Learning Foundation, summaries the need of the ELP succinctly by drawing focus on the three basics: “Early grade literacy programmes need to include children’s languages in the instructional design, keep a strong focus on oral language development and build on children’s local contexts and experiences.”[10]

Teachers engaged with Early Literacy Programme, I sincerely hope, will build upon the learning gain during pandemic by providing opportunities to students to express their experiences with the hard truth of life and survival in the last two years. This will give them confidence that their memory of alphabets may have faded a bit but their comprehension and understanding embedded in orality has become deep rooted. This orality needs to be strengthened and built upon. Also, they must realise thatinclusion of children’s home languages in the teaching and learning process is crucial for promoting language comprehension. It provides an authentic scaffold for learning the language of instruction. But what is most crucial is that use of home language promotes self-esteem and confidence for learning.

Once this is achieved, language learning will really become part and parcel of life rather than an act that happens only in the school. It is baffling though that more than four decades after the idea of ‘Emergent Literacy’ came about producing a rich study to reinforce this understanding further, the mainstream ELP practices remains stuck and frozen in ‘old thoughts. The clamour about ‘learning loss in terms of children having forgotten the ability to read and write’ (which is nothing but their ability to ‘decode’ letters or words) makes front page headlines even today. Would it not be a great idea to focus on children’s learning gains in terms of higher order thinking and enriched orality soaked into the realities of life to pick up and strengthened in the day-to-day practices of ELP and weave them around Emergent Literacy ideas?

References:

[1] The Unfolding of Language: The evolution of mankind’s greatest invention, arrow books, 2005, p.210. Anyone interested to discover the inner structure, beauty and amazing world of language needs to read this book.

[2] Ibid, p. 2

[3] Sound–meaning association biases evidenced across thousands of languages (cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com)

[4] She also designed elegant experiments to show that syntax is hard-wired into the human brain. See this beautiful obituary piece in the New York times about her work, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/27/science/lila-gleitman-dead.html

[5] https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1998/02/16/babies-quick-to-dissect-speech-research-shows/

[6] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED540491.pdf

[7] Early Literacy and Multilingual Education in South Asia | UNICEF South Asia

[8] (99+) Emergent Literacy as a Perspective for Examining How Young Children Become Writers and Readers | William H Teale and Elizabeth Sulzby – Academia.edu

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergent_literacies

[10] https://www.worldliteracysummit.org/speaker/dhir-jhingran/?utm_source=pocket_mylist